Two men, possibly in their early to mid-fifties, sat across from each other. Excitement, concentration, and wit were plastered on their faces.

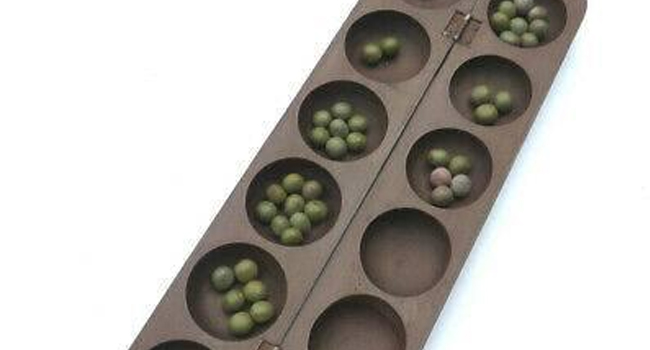

They are hurdled over a wooden board whose surface is punctuated by 12 hollows – each containing a cluster of ash-coloured seeds – amid the watchful eyes of an interested audience, who would have loved to be the participants.

“Wait!” someone echoed from the sea of faces watching seeds move on the board like a bouncing ball.

For such a friendly competition, the atmosphere is extremely fierce. Even the motorcycle riders, known as “okada” in Nigeria, who ferried people to the venue and packed a couple of metres away, were not eager to leave.

The board felt like a celebrity, as Johnson Adeoye, wearing a blue shirt with yellow stripes, looked up to acknowledge promptings from the audience; like a grandmaster, he dipped his hand into one of the hollows in the brownish wooden board to pick up some ball-like seeds.

In a swift anti-clockwise move, he deftly began to drop seeds in the adjoining hollows, emptying them in a frenzy as he raced to victory in a cosy evening at Otutu Street in the ancient town of Ile-Ife, Osun State.

This is Ayò Olọ́pọ́n – as it is referred to in the Yoruba-dominated South West of Nigeria – the African board game on a quest for Olympic recognition.

Played in many parts of Nigeria and beyond, the game is similar to the Endodoi of the Maasai people of Kenya and Tanzania and belongs to the family of Mancala board games.

In the literal sense, Ayò Olọ́pọ́n means “the game of the wooden board” in Yoruba, one of the widely spoken languages in Nigeria.

‘My Talent Is From God’

“I am a talented man. I was 13 years old when I started playing the game. I did not learn it from anyone,” Johnson, who became the first Ayo gold medalist when the game was introduced at the 11th National Sports Festival, held in Imo State in 1998, said.

“One day, I just called my dad and told him, ‘Let me play this game with you!’ and I defeated my dad 12-0.”

“I did not have any coach to train with. My talent is from Almighty God. Nobody trained me. In my family compound back then, they played the game.”

Across the country and beyond, Ayò Olọ́pọ́n is known by different names. Among the Igbos, it is called “Ncho,” or “Okwe”.

In other West African countries like Ghana, Senegal, etc, and in the Caribbean, the strategy game is known as Aware/Oware and Wari respectively. A similar one in South Africa is called Maruba. The Kenyan version is referred to as Bao.

How Ayò Olọ́pọ́n Is Played

The different names seem to point to one thing – difficulty in singling out an ethnic group or country as the originators of the game. This is even further compounded by the fact that Ayò Olọ́pọ́n is sometimes played in slightly different variations in Africa and elsewhere.

But for the Yorubas, a historian, Dr Akin Ogundiran, noted that two types of materials – a twelve-hole rectangular wooden box and 48 Ayò seeds, which are now made of marble or plastic-like seeds, are used for the game.

“Four seeds are placed in each hole. Only two people can play the game, and each player will have six holes on his/her side-24 seeds for each player. Two individuals take turns to play the game by distributing the seeds from one hole into the other holes in an anti-clockwise direction,” he explained, describing it as “what we call sowing. If there are three or fewer Ayò seeds on the opponent’s side, the player collects those.

“The players take turns to play until they exhaust the seeds, or it becomes practically impossible for one of the players to make any move. The goal of the game is to capture as many seeds of the opponent as possible. The player with the most number of seeds wins the game.”

Worried by the lack of adequate records pointing back to Africa as the origin of the board game, a member of the Osun State House of Assembly, Babatunde Olatunji, fears that the continent could lose this “part of our cultural heritage”.

“I can foresee in the nearest future, we may not be too surprised to have seen history being rewritten and somebody proving to us that Ayò Olọ́pọ́n does not also emanate from us,” Babatunde stated in a phone interview.

The lawmaker says that even the little evidence about the game has not done much in that respect. Most of the research into the origin of Ayò Olọ́pọ́n were carried out by people outside the continent, he added.

Going To The Source

In trying to trace the origin of the Ayò Olọ́pọ́n, Dr Ogundiran admitted that it is played in several parts of the world but did not mince words in pinpointing where it emanated from.

Ayò Olọ́pọ́n is pervasive among the Niger-Congo peoples – from the edge of the Sahara in Senegal to the rainforest of Central Africa and from the coast of West Africa to the beaches of East Africa, the historian noted.

“We can make a strong case that the game originated from the ancestors of the present Niger-Congo-speaking peoples, the largest language family in Africa,” the professor of Africana Studies, Anthropology and History at the University of North Carolina, told the media.

“The game spread with the expansion of those ancestors from their savanna homeland (present-day Senegal-Mali-Mauritania boundaries) into the rainforest between 7,000 and 3,000 years ago,” he said, explaining that “it reflects advanced cognitive and quantitative skill sets about the time that many people in West Africa (proto-Niger-Congo ancestors) began to adopt agricultural subsistence, farming communities, and settled life, 7,000-5,000 years ago.

“It is a game that every country in Sub-Saharan Africa should elevate to the status of national heritage. As we know, many social innovations and even technology began with games.”

Beyond the African shores, Ncho is quite popular in the Caribbean where it is better known as Wari.

During the Middle Passage – the forced movement of millions of Africans to the new world (Americas) – which lasted from 1518 to the mid-19th century, the enslaved Africans took along with them their cultures.

Ayò Olọ́pọ́n, just like many of the Niger-Congo languages and culture, was taken to the Caribbean by these Africans, Dr. Ogundiran explained.

‘Central Role In History’

The game is an integral part of the lifestyle in most communities in Nigeria. In many towns and villages, it is a common sight to see people gather under shaded trees in the evenings, playing Ayò Olọ́pọ́n after the day’s job. At other times, the elderly converge at palm wine joints known as ilé ẹlẹ́mu in Yoruba, engaging each other in the game.

Aside from adults, children and teenagers also have a thing for Ayò Olọ́pọ́n. In some rural areas, kids of varying ages usually gather in village squares to prove their mettle.

Beyond its recreational value, Ayò Olọ́pọ́n – just like most seemingly mundane things in the continent – has some spiritual undertones. This informs why it is an integral part of some festivals in certain communities in the South West. For instance, it is one of the highlights of the Osun Osogbo Festival in Osun State where winners go home with various prizes.

“The spirituality of Ayò Olọ́pọ́n derives from its central role in our history. It connects us to the past and the deified ancestors who invented the game,” added Ogundiran, who is also the Editor-In-Chief of the African Archaeological Review.

“In another vein, Ayò Olọ́pọ́n is a game where the character (ìwà), patience (ìfarabàlẹ̀), insight (ojú-inú), and deep thought (àròjinlẹ̀) are molded. Those who excel in the game are called ọ̀ta (the knowledgeable ones), and the losers are òpè (the ignorant). The game shows how much premium the Yoruba and other African groups place on knowledge and competitiveness.”

“So, to understand [some]aspects of African social organization, recreation culture, and modalities of social interaction, the codification of work and leisure, we need to pay attention to Ayò Olọ́pọ́n,” Professor Ogundiran explained.

Olympics Dream And Hurdles Ahead

Ayò Olọ́pọ́n, like many traditional African games – Dambe, Kokowa, and Langa, etc – does not have the glamour and interest generated by games like football, basketball, and tennis to name a few.

Observers believe it has not been given the recognition it deserves and may go into extinction.

“I was more concerned at some point in time because the game [Ayò Olọ́pọ́n] is no longer visible as it was before,” the Osun lawmaker, added. “I hardly see people playing Ayò Olọ́pọ́n.”

According to him, if Americans are laying claim to basketball while Europeans/Brazilians see football as their own games, nothing stops Africans from pitching their tents with Ayò Olọ́pọ́n and other traditional sports.

As part of efforts to raise more consciousness about the game, he now hosts a yearly Ayò Olọ́pọ́n competition in the South West state and his major focus is younger people whom he believes should tap into the potentials of the board game.

“Ayò Olọ́pọ́n can be well-branded and made to be so attractive to take a fair share of the multi-billion-dollar board game industry,” he said.

With Nigeria’s unemployment rising from 27.1% to 33.3% in the fourth quarter of 2020, according to the latest data released by the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) mid-March 2021, he says rebranding Ayò Olọ́pọ́n will make it a money-spinner.

“I see it as a game that can create jobs. Can you imagine we have a league on Ayò Olọ́pọ́n! Those who come to play, we have to kit them,” he added. “So, people [can] make materials and make money. You can have caps branded as Ayò Olọ́pọ́n; your favourite teams, you can have their T-shirts; you can have their caps.”

Already, the game is played in various competitions at local and international levels. At the National Sports Festival – Nigeria’s “Olympics,” Ayò Olọ́pọ́n features prominently and is a medal-winning sport.

The Chief Whip of the Osun Assembly, however, dreams big for Ayò Olọ́pọ́n.

“One of my wishes is to see the game being played in the Olympics someday,” Babatunde, who represents Ife North further stated, hoping that it would also be “credited as a game that came from Africa; to be seen as Africa’s contribution to the world.”

But there are some hurdles ahead.

Before a sport is approved for the Olympics, it must be vetted by the International Olympic Committee (IOC), and there are myriads of rules set by the 99-member body.

First, a sport must be governed by an International Federation (IF).

“This is required in order to conform to the Rules of the Olympic Charter, the World Anti-Doping Code as well as the Olympic Movement Code on the Prevention of Manipulation of Competitions,” read a statement on the Olympics website.

“It must also be practised widely across the world and meet various criteria,” another post on the Olympics website, explained.

“After that, the IOC‘s Executive Board may recommend that a recognised sport be added to the Games programme, if the IOC Session approves it.”

Also, the multiplicity of traditional games across the continent is one area that must be worked on for these games to have higher chances of making it to more international competitions, the Nigerian Traditional Sports Federation, explained.

“Let us come together in Africa to agree on the sports we want to sell,” the secretary-general of the federation’s caretaker committee, Ahmed Libata, said in an interview.

“Traditional sports are practiced everywhere; they [games] are in every country and every country has their own peculiar sports.”

Libata said that although some traditional sports like Langa, Kokowa, and Ayò Olọ́pọ́n are predominant in many countries in Africa, the same cannot be said of other games which he reiterated are peculiar to certain nations.

According to him, the federation had resorted to decentralising traditional sports competitions in the country, limiting them to areas where they are dominant.

“That is why we have to [organise] maybe Ayo [competition in Ibadan; Kokowa in Kaduna; Dambe in Katsina; Langa in Gombe; Abula maybe in Delta or Bayelsa,” Libata stressed. “We have to at least try to decentralize them so that they will be easier to organize.”

He said competitions – in Nigeria and beyond – in various traditional games are held regularly as part of efforts to grow them. Traditional games like Ayo, the caretaker scribe insists, are played in most communities in the country, noting that the federation and the Federal Ministry of Youth and Sports Development are adopting a grassroots approach in scouting for talents.

“I know they (talents) are everywhere. That is why we are trying to decentralise some of these sports in our zones,” the scribe continued.

“So, when we find that the athletes [for a particular traditional game] are predominant in a zone, we try to put a competition in that zone so we can bring out our talented youths.”

Contrary to opinions, he maintains that Ayò Olọ́pọ́n and several traditional games are quite popular especially among the younger generation but agreed that branding is required to take the sports to the global limelight.

“If you see some of the games that make it to the Olympics, they are just traditional games that have been packaged and branded well,” Libata admitted.

“And I see some of these games [traditional games] as what can be put on the global sphere; we will package them and brand them so well.”

‘No Sponsor To Support Us’

Johnson, who has featured in many Ayò Olọ́pọ́n competitions, agrees that the game needs “promoters”. He said prior to the All African Games in 2003, an exhibition tournament was held for Ayò Olọ́pọ́n as part of efforts to include it in the competition but “we have not heard anything again!”

“It is painful because this Ayo game is played all over the world. It is played in Afghanistan; it is played in Turkey; they play the game in Brazil, it is played in Trinidad and Tobago.

“And there is no sponsor to support us. That is the biggest challenge we are facing now,” the Osun State-born player, who featured in his first Ayò Olọ́pọ́n competition in 1987, told Channels Television.

“I will be glad if the Ayo game is introduced at the All African Games or Olympics; our Traditional Sports Federation in Nigeria is working to ensure that in the next All African Games, Ayo would be introduced. I would be happy if the game is introduced to the Olympics or Commonwealth Games because my plan is to play it at the festival (Commonwealth Games or Olympics; All African Games).

“The game needs more promoters and sponsors because the game is played all over the world. We need help to popularise the game.”

While he takes the game as a hobby, the player said, “We are making money through the game,” and urged Nigerians to “show more interest in the game because it is easy to play”.

Ayò Olọ́pọ́n ‘Speaks To African Culture’

Away from the need to brand Ayò Olọ́pọ́n and African traditional games in general, Ogundiran, a former lecturer at the Department of History at Florida International University, Miami in the US blamed “colonial mentality” for the seeming lack of interests in local sports among Africans especially the younger generation.

He faulted Africa’s mode of socialisation, wondering why youths should respect their cultural heritage if the older ones see it as nothing.

“If Ayò Olọ́pọ́n is played in schools and there are inter-class and inter-school competitions, I am sure the game will not lose its relevance. We play draft and chess; why not play a game that speaks to the deep-time African history and culture?” the lecturer wondered.

“Africans suffer from a colonial mentality. We tend to neglect what makes us human and embrace what dehumanizes us.”

‘Potential For Learning’

Ogundiran is not the only one to have linked Ayò Olọ́pọ́n and other traditional games to learning institutions.

Research has connected African indigenous games to improved cognitive, arithmetic, and general problem-solving.

Dr Rebecca Bayeck, who holds dual-Ph.D. in Learning Design and Technology and Comparative International Education, reviewed five African board games while trying to see if they held any educational potential.

Her research – A Review of Five African Board Games: Is There Any Educational Potential? – was published in the Cambridge Journal of Education. She found out that playing Oware, another version of Ayò Olọ́pọ́n teaches strategic thinking and arithmetic. The game, she explained, also teaches patience, spatial thinking, negation, and decision-making skills among others.

Findings from the study also suggested that the mechanics of the game showed that it could prove handy in biology. Just as the cell, Oware is characterised by a series of cyclical, repetitive movements guided by the mechanics of the game. The Oware mechanics, she continued, can be used in explaining the concept of the cell life cycle.

In his study, The Use of Indigenous Games in the Teaching and Learning of Mathematics, Professor Mogege Mosimege found out that African traditional games can change the teaching and learning of the subject.

“They do not only make it possible for learners to engage in activities that are enjoyable,” the South African lecturer wrote, “they have a great potential to help open avenues for the connection between concrete and abstract concept, between classroom environments and activities outside the classroom.”