Lotanna Igwe-Odunze wants everyone to write Igbo with freedom. The Latin alphabet, she says, has too many limitations and is a “deep source of frustration for everyone who has ever tried to read or write” Igbo. So she invented Ndebe, a script that pays homage to “the old Nsibidi logographs.”

Ndebe is not Nsibidi, she is quick to remind people. “It is completely unrelated,” she told this reporter during a 30-minute Zoom call in July. While the latter was invented more than 1,500 years ago and is generally considered too complex or indecipherable to be used by present-day Igbo people, Ndebe is designed to “overcome the design problems” of a writing system “every Igbo person could use simultaneously.”

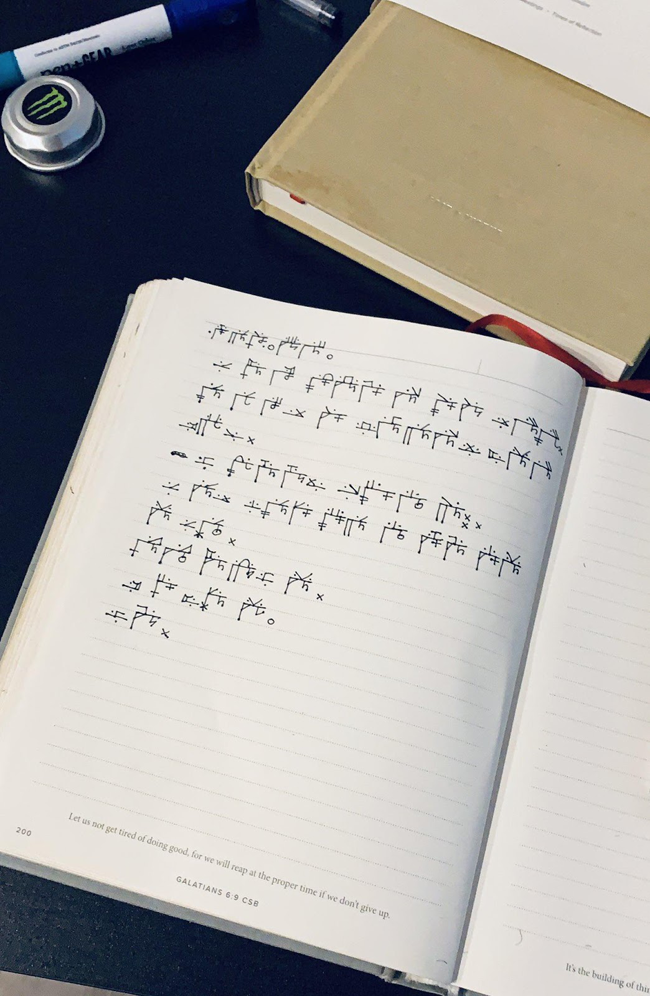

The Ndebe script is visually striking. It consists of 1,174 characters, each of which represents a particular sound in Igbo. People necessarily don’t have to memorise all the characters to be able to read or write the script because there is a formula, a scientific logic – consciously embedded by Lotanna – to ease the difficulty of assimilation, especially for busy adults.

Ndebe solves two important problems of Igbo language literacy. One, it eliminates the confusion that often arises when two Igbo speakers with different dialects try to communicate via the written page. Two, it forces Igbo to be written with the appropriate tones.

Ndebe is “a writing system that addresses the tonal peculiarities of Nigerian languages, pleasing to the eye, which might carry the burden of our literary and academic aspirations,” linguist Kola Tubosun wrote recently.

Tubosun, whose work with Yoruba won him the Premio Ostana prize in 2016, also sees Ndebe, partly on the basis of its “visual allure”, being “used along with English or other language texts on signposts throughout the country.”

“ . . . where I think the script most succeeds is in its opening of a new vista for the revitalization of Igbo as a written language both on the page and on the web, for literacy, and for culture,” he wrote.

At some point, early this July, more than 300 people were tweeting about Ndebe. Lotanna had just unveiled the new script on a dedicated website. “This is brilliant,” one person tweeted. “This should be widely adopted.” Others praised Lotanna’s brilliance. “Oyinbos lied to Africans with Western education & we all believed without doing research,” another person wrote. “They said Africans only have oral history and no form of writing. Ethiopians have Geez script and southeast Nigeria had Nsibidi which is 4000yrs old, thanks @sugabelly for educating us all.” The excitement was palpable.

When Lotanna started working on Ndebe in 2008, she was 19, studying Business Administration at Canisius College, a private Jesuit university in Buffalo, New York. The school had a lot of international students. “I used to hang out with a lot of Japanese students,” she said. Her Japanese communion piqued her interest in the East Asian nation’s culture, enough to begin considering learning Japanese.

Lotanna was a linguistic prodigy. As a child, she spoke Igbo and English, learned Yoruba in primary school, Hausa in secondary and taught herself Spanish. But it was Japanese, with its syllabic writing system, that crystallised her frustration with how African languages, especially her native Igbo, were written.

“Ever since I first learned to write Igbo in school, I have been infuriated with Samuel Ajayi Crowther,” she blogged in 2009. “The Roman system of writing was obviously never designed to accommodate African languages, but Mr. Crowther nevertheless proceeded to use it to write down all three major Nigerian languages, thereby bringing untold agony and exasperation on all future generations of young Nigerians.”

“For the Roman script, the tone marking is a big issue for me, especially because of Yoruba and the way we write,” Tubosun said during a phone interview. “There is also the technology, when we don’t have the tools to write it.” For example, Unicode is famous for incorrectly rendering certain Yoruba vowels. “So maybe if we have some other way of writing that can bypass the obstacles that Unicode presents. It might give us a new way of writing these languages.”

Lotanna started to research African writing systems and found out about Nsibidi which originated from the Cross river valley (south-east Nigeria) and consists of inscriptions in sanctuaries and special forms of language used among members of certain secret societies.

Precolonial sub-Saharan Africa is largely perceived, by western sources, as without a history of writing systems. But systems such as Nsibidi and Gicandi from the Kikuyu of Kenya, even if arcane, say otherwise. The Ge’ez script has also been in use in Ethiopia since 500 B.C. Since the 1800s, more African scripts – Mende in southern Sierra Leone, Loma in northern Liberia, Bamum in Cameroon – have been devised to perpetuate local lingua.

Armed with the knowledge that it was possible to create a writing system unique to Igbo, Lotanna, in 2008, started work.

At first, she planned to revive Nsibidi and supplement it with Ndebe. So, Igbo would be written in two scripts. (Japanese is notably written in three)

She completed the first iteration of Ndebe during the American winter break of 2008, bleeding into 2009 when she first wrote about the project on her blog. Then she was 20 and wanted to start an “Igbo Academy”.

“My goal is for the Igbo Academy to expand Igbo vastly by developing additions and modifications to the Igbo language that will greatly encourage its use in everyday life by Igbos and non-Igbos alike, and that will make Igbo relevant and expansive enough to be regularly used in business, politics, fashion, news, literature, dialogue, and in every other sphere of life,” she wrote at the time.

But her blog posts gained little traction.

“I was a bit naive,” she told this reporter. “Everyone said it’s a great idea, but nobody wanted to do the work.” When she posted it on Nairaland, a Nigerian digital newsboard, “a lot of people insulted and laughed at me. Especially a lot of Igbo people. They said this is rubbish. And I got into very heated arguments with people over it. So I ended up doing all the work by myself.”

After designing the Ndebe script, she started researching how to create new symbols from Nsibidi, posting online, looking for help.

But, around 2011, she concluded that Nsibidi was not suited for the kind of script she wanted. Like Chinese, Nsibidi characters represent an idea. So it was quite possible that there would be no limit for the number of characters to be created. In its present form, the Chinese script consists of over 50,000 characters. If her project was going to be successful, she reckoned, “it had to be easy for people to learn.”

So she went back to the initial Ndebe script she had worked on. “In its original form, Ndebe was designed as an assistant to Nsibidi. So I had to start from scratch and re-designed the whole thing.”

Some of the big changes she made was to move from an alphabetic system to a syllabary, which is harder to learn. To compensate, she worked in a formula to write the script.

“The way Ndebe works is that there is a scientific logic to how you put the pieces of the characters together,” she said. “And so because of that, when you are reading or writing Ndebe, you don’t have to have memorised the entire script. You basically have to follow the logic, and you can use the logic to understand.”

She also left out many of the design flourishes of the initial script. “The original script is a lot more beautiful than the published script,” she said, a touch of sadness in her voice. “I had to sacrifice elegance for simplicity.”

Stanley Eke, a technology entrepreneur, had seen the earlier versions of Ndebe. “At that time, it looked complex and hard to grasp,” he told this reporter. But after Lotanna published the new script in July, he practised for two hours and wrote her a ‘thank you’ note in Ndebe. “Not super accurate and I missed the ‘m’ end syllable in the first sentence,” he tweeted. “But okay enough, I think.” She was floored. “I can’t get over how quickly you adapted to writing it,” she replied. “This is amazing.”

Eke, who continues to perfect his understanding of the script, said Ndebe should become popular in the Igbo language community.

“It is authentic,” he stressed. “This is an Igbo woman who came up with this. One of ours came up with it. It simplifies the language and makes it easy to standardise, and it gives the language a visual identity. This is how Igbo should be written.”

But how many will write with it? When this reporter reached out to a few Igbo writers and educators, it was the first time they were hearing of Ndebe. “Never heard of the new script,” one award-winning Igbo author texted in response to an interview request.

“That people don’t know about it is an issue, but it’s not a big issue,” the linguist, Tubosun said. “I assume that scripts that are invented take time before they become widely accepted.” One, it has to find its way into popular culture in vehicles such as film, music, books, visual art; and, two, it has to be standardised by academics, enough to be teachable in classrooms.

“So there’s a lot of work for the inventor to do and for people who care about it as well.”

Lotanna, Ndebe’s inventor, has slightly different ideas on how she wants the script to be adopted.

“A lot of people have said, we need to get into the educational curriculum or develop some computer program with this,” she said. “I actually don’t believe that we do. I think that adoption takes personal effort. And what I’ve noticed is that a lot of people are lazy. People don’t want to make the effort to do things. They kinda just want to snap their fingers and just want it to appear. And what I want with this script – there are cultural aspirations behind it as well, otherwise I won’t have spent 11 years of my life developing it – I want to spark a change in attitude amongst people. I am trying to foster the attitude that making the effort is important. I made the effort to improve the way Igbo is written, and in return I would like to see individual Igbo people making the effort to master the script. And they should do that outside of a certain cultural pride. Not about ‘what’s in it for me’ or ‘trying to make a quick buck’. Writing in Ndebe should be its own reward. You should get a sense of enjoyment from expressing yourself using the script.”

She has put out a copyright notice on the script and has said ‘no’ (“My standard response”, she calls it) to people who have approached her to feature the script in some elaborate project.

“Because a lot of people who have made the requests haven’t taken the time to learn the script,” she added.

“The uses I’ve been most interested in, ever since I’ve launched the script, is to see individual people on Twitter who are taking the time and effort to learn the script. That has been very heartening for me to see. We’ve also had a writing competition. People got out their notebooks and pieces of paper and wrote a few sentences. Some people even wrote like a whole page. And that’s an amazing effort.

“A lot of people are kinda jumping the gun.

“The whole point of the Ndebe script is, it is supposed to be for everyone’s private, daily use. You want to write a letter, use Ndebe, you want to write a grocery list, use Ndebe. If you want to jot down your daydreams, use Ndebe. If you want to write in a diary, use Ndebe. And I think that these uses of the writing system are far more important than commercial uses that seem flashy and after a while, everybody loses interest.

“How a language gets passed on and persists into the future, is not through the flashy uses of the language, it’s through the boring, daily use of that language. And that’s what I really want people to focus on.

“I don’t mind if, in terms of adoption, progress is slow. I care more about the quality of progress that we are making.”

Whether her approach is the right one is anyone’s guess, but her journey is evidence enough that she’s in it for the long haul.

“I do feel relieved that I’ve done it and it’s out,” she said of the script’s release into the world. “But there’s still quite a lot of work to be done. And it’s like there is definitely a weight on my shoulders, because now that the general public knows about the script that I’ve invented, I also have the responsibility to ensure that the script is being used in a way that I envisioned, and to guide the project to fulfil its goals.

“There are goals that I’ll like to be fulfilled in terms of adoption, digitization, the use of the script, reforming the Igbo language. I do think that it might be something of a lifelong project for me.”